Preview: I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets

By Fletcher Hanks (compiled by Paul Karasik)

Fantagraphics, 2007, $19.95

For a sneak peek into the brain of one of comics’ original weirdos, all you need is to learn the source of the title to this collection. Set almost perfectly in the middle of a dozen or so tales from the pen of Fletcher Hanks (or Henry Fletcher, or Barclay Flagg, depending on whether Hanks was in the mood to use a pseudonym) is a space opera. Buzz Crandall and Sandra Hale of the Space Patrol learn of a plot by Lepus the Fiend, a hairy guy who only wears green pants, to wreak havoc with his secret ray.

For a sneak peek into the brain of one of comics’ original weirdos, all you need is to learn the source of the title to this collection. Set almost perfectly in the middle of a dozen or so tales from the pen of Fletcher Hanks (or Henry Fletcher, or Barclay Flagg, depending on whether Hanks was in the mood to use a pseudonym) is a space opera. Buzz Crandall and Sandra Hale of the Space Patrol learn of a plot by Lepus the Fiend, a hairy guy who only wears green pants, to wreak havoc with his secret ray.

Lepus says: “I shall make all the universe wild and primitive! I shall destroy all the civilized planets!”

But, fear not, the space guardians prevail, and Lepus dies a terrible death, crushed in the rubble of his destructive dreams. This is essentially every Fletcher Hanks story rolled into one. Working in comics in the medium’s earliest era (1939-1941), Hanks wrote and illustrated bizarre and nonsensical worlds, in which exposition serves only to further confuse. The plot, though, is simple and always the same: bad guys do something very bad, heroes save the day, fitting justice is inflicted.

One might wonder, then, why Hanks has become a hero of the comic book aficionado (finally now with a handsome collection fitting his esteem). It certainly doesn’t hurt that his works are old and rare, often the only qualification collectors need to drive up the value of someone’s work. But, beyond the good fortune Hanks had to work in the golden age and not enjoy much popularity, his work is strangely good in the way that Plan 9 from Outer Space is savored: Yes, Hanks is indeed the Ed Wood of comics.

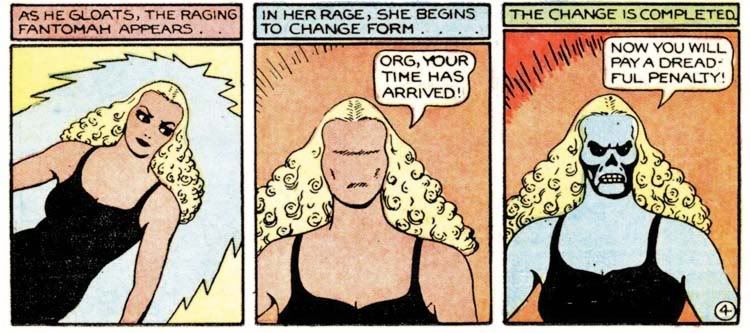

The perfect summation of Hanks’ insanity can be seen in the above panel, which features “Fantomah,” a guardian princess of the jungle. A villain has loosed giant spiders onto the serene land. Fantomah becomes pissed, and the only thing more bizarre than a very Caucasian blond woman lording over a foreign jungle is that she deals with problems by turning into a female Skeletor and devastating her foes with unseen powers.

In addition to Fantomah, the other character featured most regularly is Stardust, a crime-fighting sorcerer from outer space. Stardust just floats around above the world, using powerful crime-detecting equipment and attacking once dastardly deeds commence. Criminals commit such atrocities as gassing all of humanity, or stopping the earth’s gravity so that everyone but them floats off into space to die.

The imaginative nature of these criminal plots are only exceeded by the creative ways Hanks comes up with to dispatch of the criminals. And that, in a very macabre way, is what truly sets Hanks apart. It almost seems like every story he sets out to best his previous conclusion. We go from villains suspended in the air beside the skeletons of their victims to villains turned to monsters and eaten by giant spiders to villains transported to a barren island and eaten by a giant, golden octopus to villains frozen in space prisons so they can contemplate their actions for eternity to my personal favorite — a villain turned into a giant head, then thrown onto another planet where he’s absorbed into the body of a headhunter (which is a giant alien with no head).

The imaginative nature of these criminal plots are only exceeded by the creative ways Hanks comes up with to dispatch of the criminals. And that, in a very macabre way, is what truly sets Hanks apart. It almost seems like every story he sets out to best his previous conclusion. We go from villains suspended in the air beside the skeletons of their victims to villains turned to monsters and eaten by giant spiders to villains transported to a barren island and eaten by a giant, golden octopus to villains frozen in space prisons so they can contemplate their actions for eternity to my personal favorite — a villain turned into a giant head, then thrown onto another planet where he’s absorbed into the body of a headhunter (which is a giant alien with no head).

Hanks’ work is the black hole of sense-making, but damn if it isn’t fun to read. And while I don’t subscribe to the belief that comics are inherently more worthwhile if they’re older, I would say that knowing the era in which Hanks was producing these comics makes his dark imagination even more appreciable. His work is most certainly not good (beyond the strange use of colors that sees an orange earth floating in purple space, he almost always forces airplanes into his stories, I assume because they’re easy to draw), but it’s maniacally enjoyable. What’s surprising, then, is how Karasik nearly steals the show with the epilogue, an illustrated account of how he tracked down Fletcher Hanks Jr.

All in all, this volume is a fitting (see: inane) tribute to an enigmatic creator who was not before his time, because the works of Fletcher Hanks belong outside of time and space, in a dimension all their own.

Cool site!