It’s official: the Skrulls are Muslims

I have no problem with superhero comics drawing from real world events in their fictional worlds. I would actually probably argue for it, particularly in the Marvel Universe, which has always been more of a real-world application of superheroics.

Secret Invasion clearly had some roots in the post-9/11 terrorist paranoia, particularly with the Skrulls’ presence being announced by way of exploding skyscrapers and attacks on military facilities. Secret War was not subtle in its 9/11 connections.

Secret Invasion always had a religious component to it, but when Secret Invasion #6 made it clear that the “He” who loves the Skrulls is “God,” it took the tribute to the headlines to another level. Even then, though, there was still some ambiguity and room for discussion. The Skrulls’ invasion, at that point, was just as related to the Crusades or Manifest Destiny as it was to modern-day religious extremism, and that is what makes these real-life connections most interesting — the ability to look at the comic symbolism and apply it in multiple debatable ways.

Where these allegories have great potential to fail is where they become too specific and too tied to the headlines. Imagine if Civil War had gone far enough to actually make one side of the superhero registration act Democrats and one side Republicans — it would’ve killed it. The fun of Civil War was in looking at the pros and cons of both arguments, independent of the struggles and failures of the heroes who took those sides. It was easy enough to make inferences about the partisanship, but it let the themes transcend the real-life issues so they could be fully applied to the fictional ones (and vice versa).

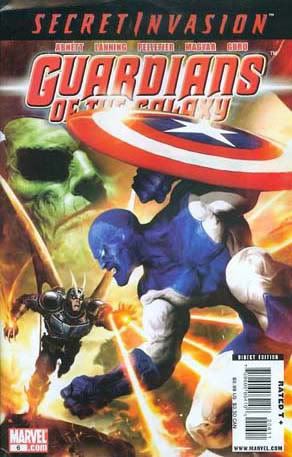

So no, obviously nobody came out and said “the Skrulls are Muslims.” But what did happen is that in Guardians of the Galaxy #6, some conscientious objectors referred to the Skrull leadership as “the Jihadist regime.” If one were to give Marvel the benefit of the doubt, maybe the writers and editors took “jihad” to be some kind of catch-all generic term for holy war with no specific ties to Islam. One, they should know better, and two, it doesn’t take very long to double check.

So no, obviously nobody came out and said “the Skrulls are Muslims.” But what did happen is that in Guardians of the Galaxy #6, some conscientious objectors referred to the Skrull leadership as “the Jihadist regime.” If one were to give Marvel the benefit of the doubt, maybe the writers and editors took “jihad” to be some kind of catch-all generic term for holy war with no specific ties to Islam. One, they should know better, and two, it doesn’t take very long to double check.

What this does, by overtly tying the Skrulls to militant Muslim extremists, is eliminates the opportunity for multiple applications of the symbolism. As stated above, Manifest Destiny and the Crusades were probably equally applicable to the Skrull Invasion if not moreso due to the role that particular land played in those “holy wars” of the past. For example, the premise of the Skrulls arriving as peaceful benefactors who just want to share the land was one of my favorite parts of Secret Invasion due to its parallels with the Americans they sought to colonize. Now, any allegorical life that element may have had is essentially rendered inert.

The ambiguity was clearly intentional, as Marvel’s marketing over the past two years has been “Whose side are you on?” and then “Who can you trust?” The fun is in thinking about the questions; the craft is in making us want to think about it; the art is in letting readers apply it to their daily lives.

I have no problems with readers who read Secret Invasion and thought “Oh, the Skrulls are kind of like Al Qaeda,” just like I have no problem with someone who thought “Oh, the Skrulls are kind of like John L. O’Sullivan and the Jacksonian Democrats!” Nor do I have a problem with Marvel making the Skrulls the bad guys and the conscientious “pro-human” objectors the good guys. What I do have a problem with, on both a social and artistic level, is Marvel telling us who the good guys and bad guys are in real life.

I’d originally thought the Skrulls were an unpleasant comparison to the Jewish people. That no longer looks to be the case, fortunately, but I do think that, in current American usage, the word “jihad” has become enough of a term for any obssessive, usually destructive religious campaign that it doesn’t have to mean Muslim. Anyone on a crusade of some kind, if they appear fanatical, might be jokingly said to be on a jihad, even if their issue is not specifically religious. The word has been assimilated as slang in English; resistance was futile.

I guess I just haven’t been exposed to enough post-9/11 violent non-Muslim religious crusades to realize that “jihad” has become a catch-all term. (EDIT: I don’t mean that to be as snarky as it sounds.) Even then, as you say, if it’s “jokingly,” it makes Marvel’s usage every bit as inappropriate. I do hold a publishing company to higher standards than I do the average person on the street.

I haven’t read the issue, so in context the remark could have been more specific, but even before 911 the word “jihad” was moving past the Middle East. It probably started in sci-fi novels, for religious wars that did not necessarily take place in a world that would have Muslims, although I think in the Dune books it was still meant to include some of that association.

But as I mentioned, context makes the difference. I’d hope that Marvel could come up with a more complex social commentary than Skrulls-as-Muslims, but I’ve been let down by comics before.

Not to unnecessarily extend this discussion, but if the argument is that colloquial use of “jihad” existed pre-9/11 and therefore should be all-purpose now, I strongly disagree. 9/11 changed a lot of things, and I would think ending cavalier usage of that term would be a no-brainer.

While throwing out the word jihad definitely makes it hard to think about anything other than Muslim extremists, it’s important to remember the source. In a similar vein to that of Mr. Heffison, the term jihad doesn’t always come back to Islam, especially in today’s vernacular. People toss that word around for all sorts of reasons, frequently misusing it.

Perhaps our friends at Marvel are merely pointing out the ignorance of the speakers, or the masses in general. Just because some people in the universe think the Skrull are Muslim, doesn’t mean they are.

The speakers in question are the Skrulls themselves.

Love the name, by the way.

Skrulls, eh? I think the fact that I haven’t read the comic is fairly apparent now. Or is it? Perhaps I know far more than you can possibly imagine!

No. That’s not the case.

I’ll stop commenting now.